Keustermans started making art somewhere around 2007, this is when he was showing drawings for the first time in a group expo in Istanbul. Following that he participated every other year or so in shows, almost all of them in the Netherlands. Of course there was life before that. At the time he was 47, the first twenty odd years of which he had been drawing and painting but never exhibiting his work. Gradually he made less and less work up to a point where he forgot that could be an artist.

The art he made between 2007 and 2020 was abstract art. His modus operandi was to spend significant time thinking and devising what to do for each drawing. The actual execution usually took a day. The amount of time involved had mostly to do with the relative complexity and amount of detail.

But once the drawing started, he did what he had set out to do and nothing else.

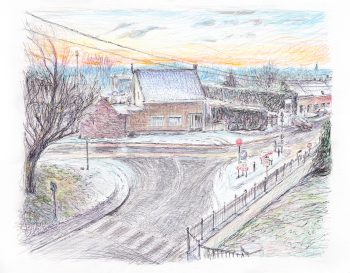

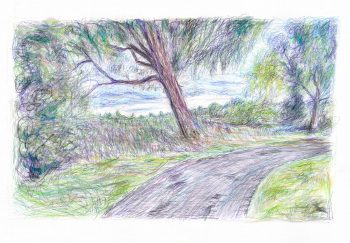

That changed with Covid in 2020. For different reasons he stopped making drawings. After a six-month hiatus, he started drawing again, going back to a much earlier version of himself, the adolescent artist who drew from nature. In his words: “I look at something, a scene in front of me or a picture and I start drawing it. Till it’s finished”. So this is the new Keustermans or should we say rejuvenated.

This is very different from the ‘old’ approach as there is no plan apart from choosing rather instinctively what to draw. Not only does this ‘new me’ spend less time on a drawing, but the work is considerably more intense, physically and mentally. There is a long series of tiny interactions between the eye, the hand and whatever the hand picks up to make the marks.

Why did he not do this just-go-ahead-and-draw before? Maybe because he was afraid that he would produce rubbish when letting go? That would explain the restrained approach: thinking, planning, musing first followed by a straight forward execution.

The act of drawing

Let’s recap. The ‘old Keustermans’ was a deliberate and analytical artist, spending significant time planning and conceptualising before beginning a drawing. In contrast, the ‘new Keustermans’ is more spontaneous and intuitive, starting without a preconceived plan.

Not only has the relative importance of planning and execution shifted, but the nature of the drawing experience itself has evolved. The focus has shifted from the mechanics of lines, colours, and tools to the act of looking, the gestures of the hand, and the overall experience of drawing. This drawing experience has become the primary driving force behind Keustermans’ work.

Next we will discuss three possible key aspects of this ‘drawing-in-the-moment’ approach: direct action, imprecision, and lack of intent.

Direct action

Both Van Gogh and Twombly’s work exemplify what could be meant by direct action.

In a letter Van Gogh wrote to Émile Bernard in 1889 he evokes this need for immediacy:

“J’ai quelquefois travaillé excessivement vite, est ce un défaut? je n’y peux rien.

Ainsi une toile de 30 – le soir d’été – je l’ai peinte dans une seule séance.–

Y revenir est pas possible – la détruire – pourquoi, puisque je suis sorti dehors en plein mistral exprès pour faire cela.– N’est-ce pas plutôt l’intensité de la pensée que le calme de la touche que nous recherchons – et dans la circonstance

donnée de travail primesautier sur place et sur nature, la touche calme et bien réglée est-elle toujours possible? Ma foi – il me semble – pas plus que l’escrime à l’assaut.”

You go at it till it is finished. No putting aside the tools and time for reflection, no distancing from the thing you’re doing. Just paint this thing.

Cy Twombly left behind very little writing, but there is a very short essay from 1957 (published in an Italian art journal) in which he says:

“Each line is now the actual experience with its own innate history. It does not illustrate – it is the sensation of its own realization”

This is very much the ‘new Keustermans’. Drawing is no longer the premeditated record of a thought or emotion, the drawing is about doing things here fueled by the experience of being immersed in that action.

Imprecision, lack of intent

These two aspects are a bit more speculative.

One can say that truth (in drawing and elsewhere) goes with clarity and precision. For instance, getting true likeness is rendering with precision what is out there. Imprecision then would be a lack of that. You do not know who or what you are looking at. But might there not be a gain in possibilities, more interpretations, more meaning if things are not clear?

It could be like a pendulum. When you are too vague there is not much truth anymore, you need to be specific. But when things get too specific, they become trivial. Nothing happens in this kind of complete drawing.

However one should not treat drawing as saying things, at least not in these kinds of drawing. So maybe when the drawing is imprecise it is not necessarily more meaningful, but it might show more. There is more space for things to be seen. More gets in. Especially things that relate to the experience of drawing. It might be impossible to put this experience into words, so one shouldn’t try to pinpoint emotions or memories or God forbid the subconscious. Leaving out all of that, the artist and viewer are still left with a lot of drawing to be seen.

But what does the viewer experience?

Well, it is hard to know. And the artist can not and should not steer the viewer.

The pleasure artist and viewer alike get from drawing is certainly not unique to art. We have experiences in the real world, not involving art, where we feel elated, happy, contented, puzzled, … something happens that we have not seen before. One summer evening you go outside and you are struck by a certain configuration of clouds. Or is the colour of the blue sky or is it rather the way high winds lay out a blanket of white fluff? You are not sure what exactly you are experiencing but you are completely immersed in this feeling, in the certainty of having an experience and it carries you further and further. Till it’s over.

Keustermans tells us that when making his drawing, he is immersed in this feeling of the drawing happening, of this eye-hand-tools thing. Not in what the drawing shows, not in what the drawing evokes, not in something about it that is most salient, most important but foremost in him doing the drawing. And that is the kind of experience Keustermans shares by showing these drawings.

Erwin Keustermans holds a Master in Philosophy at the Catholic University of Leuven and a Post Graduate Degree in Computer Science at the University of Ghent.